Bertrand Russell Warned Us About Fools and Fanatics — We Should Listen Now

From vaccines to visas, censorship to certainty, Russell’s century-old warning feels more urgent than ever.

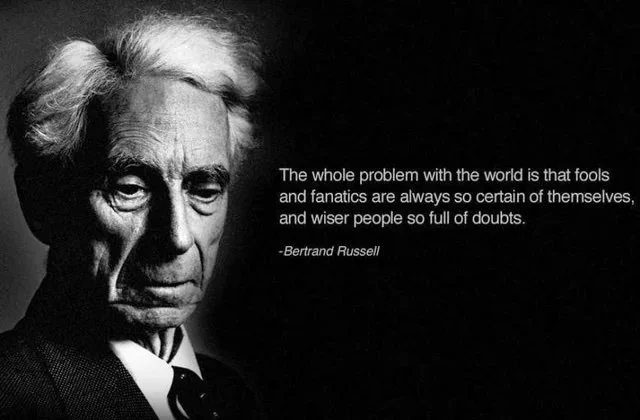

I’ve been interested in philosophy and the meaning of life for decades. One philosopher I admire greatly is Bertrand Russell. The more I learn about his life, the more I notice small, unexpected parallels with my own.

Russell was born in Trellech, in the historic county of Monmouthshire — and I was born in the same county many years later. Nearly a century after his birth, he died at Plas Penrhyn in Penrhyndeudraeth, and I now live barely twenty minutes from his final resting place. There’s something quietly moving about that — knowing that one of the most remarkable thinkers of the twentieth century spent his last years in the same landscape I now call home.

It’s easy to see why he chose this place. Penrhyndeudraeth lies tucked beneath the mountains, with the estuary stretching out towards the sea and the silence of Snowdonia all around. It’s a landscape that invites reflection — the kind of quiet that encourages you to step outside yourself and consider the bigger patterns of life. I often wonder if Russell found the same stillness here, looking out towards the hills as the century he had helped shape slowly unfolded around him.

And what a century it was. Born in 1872, when Queen Victoria was still on the throne and the British Empire stood at its height, Russell lived long enough to watch men walk on the Moon. His ninety-seven years spanned horse-drawn carriages and jet engines, telegrams and television, empire and Cold War. Few lives have bridged so much change — and fewer still have shaped it as profoundly as his.

The Making of a Philosopher

Russell’s story begins with loss. His mother died of diphtheria when he was just two years old, followed soon after by his father, and then his sister. By the age of four, he was effectively orphaned, raised under the strict care of his formidable grandmother, Lady Russell, at Pembroke Lodge in Richmond Park. The house was grand, but his childhood was marked by solitude and discipline.

That solitude turned him inward. In his later autobiography, Russell admitted that he often thought of suicide as a child, saved only by a promise he made to himself: to live long enough to discover whether mathematics might hold the key to truth. Numbers and reasoning became his lifeline. Where others sought comfort in faith, Russell found it in logic.

At Trinity College, Cambridge, he flourished. Surrounded by brilliant contemporaries, he distinguished himself as both mathematician and philosopher. Here he discovered not just the power of abstract reasoning but the exhilaration of debate — the freedom to question everything. Out of this atmosphere came his most famous collaboration: Principia Mathematica(1910–13), written with Alfred North Whitehead. It was an audacious attempt to show that all of mathematics could be built from pure logic. Even though later thinkers showed that dream to be unattainable, the work reshaped philosophy and helped give birth to modern analytic thought.

Russell the Dissenter

But Russell was never content with the ivory tower. He brought the same clarity and boldness to politics that he had to logic. During the First World War he became a vocal pacifist, denouncing Britain’s involvement at the cost of his Cambridge lectureship and a prison sentence in 1916. Later he spoke out just as fiercely against fascism, empire, and — most famously — the nuclear arms race.

He paid dearly for his courage. He was imprisoned twice, vilified in the press, and denounced as a danger to public morality. Yet he never stopped writing, speaking, and organising. In 1955, alongside Albert Einstein, he co-authored the Russell–Einstein Manifesto, warning of the existential threat posed by nuclear weapons. Out of that came the Pugwash Conferences and the broader peace movement that shaped the second half of the twentieth century.

Plas Penrhyn and the Search for Stillness

In 1955 — the year I turned one — Russell and his fourth wife, Edith Finch, moved into Plas Penrhyn, a large Victorian house just outside Penrhyndeudraeth. It became his home for the final fifteen years of his life. Today the house is still a private residence, hidden among trees, not open to the public. That feels somehow fitting. His presence lingers more in the landscape than in the walls — in the soft light over the estuary, the outline of the Moelwyn mountains, the quiet rhythms of the village.

From Plas Penrhyn, Russell corresponded with world leaders and activists, turning a quiet corner of Gwynedd into a hub of global thought. There is a certain poignancy in imagining those letters — about nuclear annihilation, peace, and the survival of civilisation — being written in a study overlooking the still waters of the Dwyryd.

Just across the estuary lies Portmeirion, the eccentric Italianate village created by architect Clough Williams-Ellis. My family and I have been members there for years, and I love its strangeness, its colour, its refusal to be ordinary. Russell would have known it well, and I like to imagine him wandering its paths, amused by its whimsy. Both men, in their own ways, were rebels against convention: Williams-Ellis reshaped the physical landscape; Russell reshaped the intellectual one.

Why Russell Matters Now

At its heart, philosophy began not in lecture halls or textbooks, but in the restless questions of people trying to make sense of life. What matters? How should we live? What is worth believing? Russell never lost sight of that. For all the technical brilliance of Principia Mathematica, he returned again and again to the simplest, most human questions: how to live with doubt, how to resist dogma, how to balance reason with compassion.

In today’s world — where certainty is shouted from podiums, where misinformation spreads faster than truth, and where ordinary people are left trying to navigate the chaos — those questions feel more urgent than ever. We don’t need philosophy as an abstract discipline; we need it as it was first intended: a guide to making sense of life.

That is why Russell still matters. His century may be behind us, but his voice still carries. Again and again, he refused the comforts of silence. He opposed the First World War when most were swept up in patriotic fervour. He challenged nuclear proliferation when others looked away. He denounced dogma wherever he found it. To the end, he kept asking: what does it mean to live truthfully in an age of fear?

That question has not gone away. Today, as the Trump administration speaks with absolute certainty on matters( they have no understanding of) as complex as vaccines, Tylenol, and visas, Russell’s warning feels painfully familiar:

“The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, and wiser people so full of doubts.”

But there is another danger Russell knew well — censorship. He experienced it first-hand, losing his Cambridge post and being jailed for his dissent. Today, when even entertainers like Jimmy Kimmel raise the alarm about voices being muted or platforms being restricted, we should pay attention. Silencing debate, whether in universities, media, or politics, does not strengthen truth — it corrodes it. For Russell, the antidote to fanaticism was never censorship, but more openness, more honesty, more doubt.

We are living once again in an age when certainties are brandished as weapons, when slogans matter more than evidence, and when truth itself seems negotiable. Russell’s reminder to “remember your humanity, and forget the rest” remains one of the most urgent challenges of our time.

For me, living just minutes from his final home, the connection feels tangible. I think of him sometimes when I drive through Penrhyndeudraeth or when I walk the paths of Portmeirion. Both places remind me that life is larger than the boundaries others set for us — that we can dissent, question, and imagine differently.

The mountains here still stand as they did in Russell’s time, silent witnesses to change and continuity alike. He looked out at them in his final years, as the world lurched from crisis to crisis, and chose to keep believing in reason and hope. Standing in the same landscape, I find it difficult not to do the same.